Layoffs have never sounded so sexy

And beating China at their own game

If you missed last week’s newsletters, catch up here and here. If this newsletter was forwarded to you, subscribe here for free:

Notadeepdive is powered by two super supportive brand partners, Credit Direct and Busha. Make sure to check them out!

TOGETHER WITH CREDIT DIRECT

Generosity is great, but strategic generosity changes lives. Gift A Yield transforms your kind gesture into a compounding investment.

By gifting a Yield plan to someone, you aren’t just giving money; you’re giving them a future they can actually use. While other gifts lose value, a Yield plan compounds. It’s strategic, it’s thoughtful, and it’s the only gift that literally pays them back. Give them a financial head start today.

When do shareholders love layoffs?

When you subscribe to Notadeepdive, the broad promise is that you’ll understand Nigeria’s tech scene without the fluff. Somewhere in the fine print, however, is your front-row seat to my healthy obsession with Jumia.

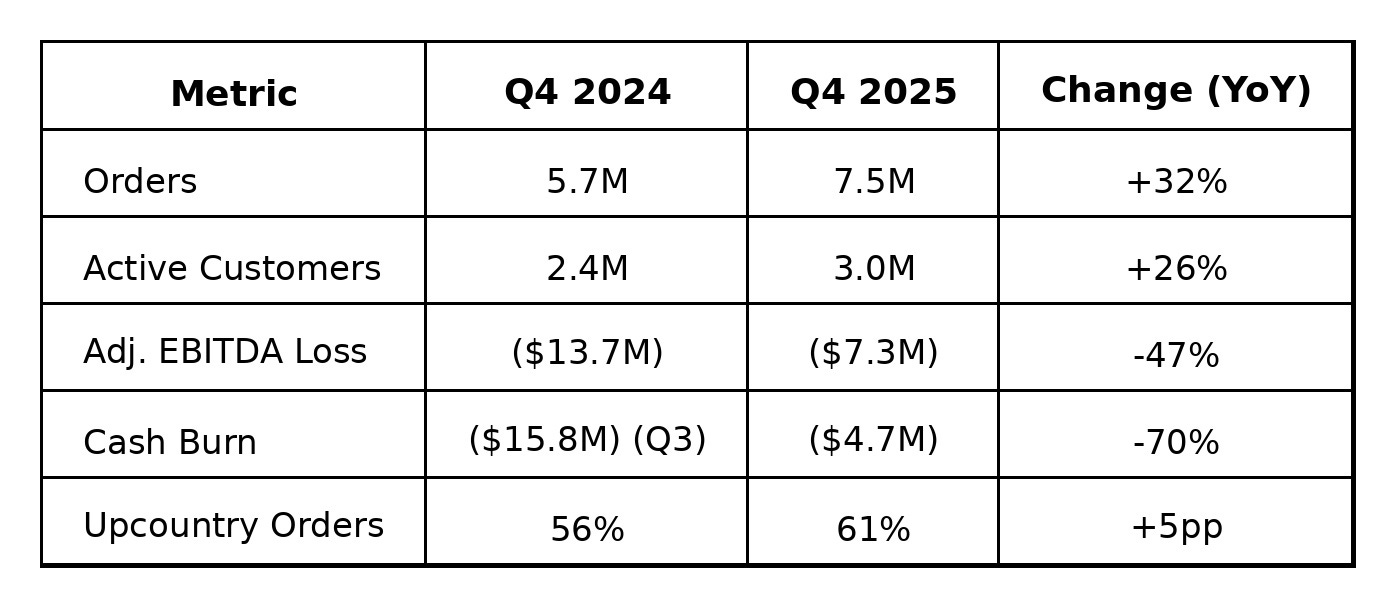

This week, Jumia released its Q4 and full-year 2025 results, so yes: Notadeepdive insiders saw this newsletter coming.

Since it became a public company, every Jumia earnings story has been a predictable song and dance: losses, losses, more losses, how-is-this-company-still-alive. The media fixated on top and bottom lines, the staggering scale of the red ink, and honestly, who could blame them? The numbers were shocking.

But a lot has changed in the last two years since Francis Dufay took the CEO job and began making the kind of pragmatic decisions that Jumia obsessives have been begging for. In 2025, he leaned into the media in a way his predecessors never did: talking more, saying the hard things out loud, not hiding behind corporate boilerplate.

When your CEO openly tells reporters he’s willing to exit countries, cut headcount, and shelve entire product lines, the narrative shifts to “this guy might actually pull it off.”

These days, Jumia is all cost discipline, China sourcing, and a CEO who sounds like he’d fire his own reflection if it wasn’t hitting its KPIs. Investors are eating it up.

When Dufay casually mentioned on this week’s earnings call that the company would lay off even more people in 2026, primarily across technology and G&A, it didn’t make a single headline.

When you’re unprofitable, layoffs are sexy.

That’s an absurd sentence if you dwell on it for even five seconds, because layoffs are never sexy to the people being laid off. But it’s an honest description of how public markets behave. When a company has spent a decade proving it can grow without any care for unit economics, markets reward the first credible signs of economics, even if the path runs through headcount cuts.

Let’s rewind a bit.

Nigeria’s early startup crop (and Africa’s, broadly) was a long parade of “X for Africa” companies—sometimes good companies, other times mediocre copy-paste operations. Jumia, founded in 2012, was the “Amazon of Africa,” backed by Rocket Internet, a firm whose entire business model was to speed-run proven ideas into new markets.

The theory was simple: there’s a huge untapped online shopping market. If you onboard enough users and burn enough VC money subsidising shopping, you eventually end up with such a large market share that you can raise prices, turn off the subsidies, and become profitable.

This famously worked for Uber. It did not work for Jumia.

By 2018, Jumia was in 14 countries, and by its 2019 IPO, it had raised $800 million. Right now, it’s rolling back on those early moves.

It has now exited Algeria (it exited South Africa and Tunisia in 2024), cutting down its operational markets to eight. It has just 2,010 employees, down 7% from a year ago.

Its highest-paid executives, who until late 2022 were sitting in a Dubai office while running an African business, have been relocated to the continent. Its cloud bill has been renegotiated. Its food delivery arm? Dead. Its JumiaPay fintech ambitions? Shelved. What’s left is a leaner e-commerce marketplace that, for the first time, looks like it might actually work.

It has only taken fourteen years, but Jumia has now found product-market fit.

“Jumia operates in markets that remain significantly underpenetrated for e-commerce,” said CEO Francis Dufay on this week’s earnings call.

Fourteen years after the company’s initial assumption that African markets were underdeveloped for e-commerce, it still sounds like day one. Not in that self-congratulatory, fake-humble way startup bros typically use the term.

The underlying numbers have improved, but you’ve got to admit that in the age of AI, shareholders hear “layoffs” and “automation” and figure a company is efficiently deploying resources. It’s even better if you’re promising full-year profitability by next year.

“The message we gave to the teams in all countries is that all business units are expected to deliver scale and profitability in a very reasonable time frame,” Dufay said. “We’re not shy of taking tough decisions.”

Big talk.

TOGETHER WITH BUSHA

If you are a business exploring digital assets for cross-border payments or treasury management, you should check out Busha Business. Busha business also allows you to buy, sell, receive, and send stablecoins and digital assets.

Beating Temu by copying Temu

One interesting subplot in the Jumia story is how it reacted to the Temu and Shein threat.

I wrote in Semafor last year that Jumia acknowledged the competition head-on and began sourcing items directly from China. It opened offices in Shenzhen and, more recently, in Yiwu, one of the world’s largest wholesale commodity markets (if you’ve bought a cheap phone case or a suspiciously affordable Bluetooth speaker at any point in the last decade, there’s a reasonable chance it passed through Yiwu). In Q4, Jumia sold 6.1 million international items, up over 80% year-over-year. It now has roughly 24,000 China-based sellers on its marketplace.

The strategy is almost comically straightforward: Jumia looked at what made Temu competitive—cheap goods sourced directly from Chinese manufacturers—and replicated it.

It also has one crucial advantage that Temu can’t easily copy: several thousand goods sitting in African warehouses, ready for next-day delivery. Temu’s cross-border model ships individual packages from China, which is fine for a $5 pair of earbuds you don’t urgently need, but doesn’t work so well when you want a fridge. Appliances, TVs, and phones make up about 60% of Jumia’s general merchandise. Good luck drop-shipping a refrigerator from Shenzhen to Maiduguri.

Dufay did a small victory lap this week: “We are seeing less aggressive behaviour from certain global entrants in selected countries, including Nigeria, while our local market share continues to build.”

On top of that, the Ivory Coast introduced a new tax on the profits of non-resident e-commerce platforms. Ghana’s VAT Amendment Act now requires cross-border platforms to register for VAT and comply with local requirements. Part of what made Temu’s pricing so competitive—not paying local taxes—is shrinking in several African markets.

Has anyone else noticed that Temu has started offering seven-day delivery on select items to Nigeria, a massive improvement on its two-week-ish shipping? In any case, they’re now on the defensive with Jumia absorbing their playbook while retaining local infrastructure advantage.

The real growth story is not in Lagos

Here’s an interesting number in the entire earnings report: orders from upcountry regions a.k.a underserved, small towns and villages with populations ranging from roughly 20,000 to 150,000, now account for 61% of Jumia’s total volumes, up from 56% a year ago.

In Lagos, Abuja or Nairobi, consumers have a dozen shopping options, and the local trader’s margin is kept in check by competition. Smaller cities have limited product selection, and whatever is available is marked up considerably.

If you went to a boarding secondary school or university outside a major city, you’ll immediately understand this dynamic.

Students would travel back from Lagos with extra products to sell to classmates at a nice markup—toiletries, electronics, snacks, you name it—because those items were either unavailable or wildly overpriced locally. It was a whole informal economy. The things people in major cities take for granted are a luxury in smaller towns.

Jumia is that student, except it has 350 pickup stations and a fleet of delivery trucks.

It’s worth remembering that Copia, the well-funded Kenyan e-commerce startup, had identified a nearly identical opportunity before it went into administration in mid-2024 and eventually liquidated. Copia focused on serving mass-market consumers in rural and peri-urban areas through a network of 50,000 agents. The thesis was sound: underserved populations, limited assortment, and high local prices. It burned through over $120 million, and the economics never clicked.

The difference, presumably, is that Jumia already has the logistics network, the brand recognition, and the warehousing infrastructure across eight countries. It doesn’t need to build from scratch in each new region. It just needs to extend the last mile.

If Jumia’s moat is really about being the best (or only) decent option in underserved cities rather than beating Temu on price in Lagos, it means the growth story is tied to the physical reality of how goods move across Africa, not a competitive cycle that could reverse when the next Chinese app shows up. It also means Jumia’s flywheel gets stronger the further it pushes from the big cities, exactly where the competition is thinnest, and the margins are fattest.

This year, the company raised commissions across most countries without vendors kicking up a storm. When you can hike your take rate, and your sellers just keep selling, it’s usually a sign of genuine product-market fit.

So, is this actually working?

“We believe that we are now in the right markets, at the right time, and finally with the right product-market fit.”

That’s a big statement from a company that has been promising profitability since roughly 2019.

It’s also a sentence that contains the word “finally,” which is doing a lot of heavy lifting. Jumia is targeting adjusted EBITDA breakeven and positive cash flow in Q4 2026, and full-year profitability in 2027. The company says its existing $77.8 million in liquidity is sufficient to get there without raising additional capital.

It’s a more credible claim than it’s ever been. But it’s still a claim. Advertising revenue, which Dufay envisions growing from 1% of GMV to 2% over the medium term, underperformed in 2025.

Dufay was candid about this on the call: “Monetisation on the advertising side is still lower than our expectations in Q4, including across the whole year, actually, and that’s the reason for deviation on the bottom line.”

The guided EBITDA loss for 2026 is still negative $25 million to $30 million, which means there’s very little room for error in the back half of the year. This is a company that needs everything to go right for the next seven quarters.

Still, the trajectory is unmistakable. Costs are structural and trending down. Revenue is growing at 34%. The China sourcing pipeline is scaling. Upcountry penetration is expanding. And the competitive landscape is, for the first time in years, moving in Jumia’s favour rather than against it.

If full-year profitability arrives in 2027, it would will have taken 15 years. That’s a long time. But for a company that was trying to build logistics infrastructure, payment systems, and consumer trust in some of the world’s hardest markets, maybe the surprise isn’t that it took this long. Maybe it’s that they’re still here at all.

See you on Sunday!

Liking and sharing the newsletter helps it travel!