Lending is easy™

What happens when staff allegedly collude to divert ₦4.6 billion?

Three weeks went by in a flash, and it’s great to be back! Thank you to everyone who wrote me.

If this newsletter was forwarded to you, subscribe here for free:

TOGETHER WITH CREDIT DIRECT

Every meaningful leap starts with the right support. A loan, when used rightly, carries you from intention to achievement.

At Credit Direct, we offer personal loans accessible on WhatsApp, USSD, or the web so you can focus on building while we back your journey.

Lending is easy™

Access Bank went to court this week to claw back ₦4.6 billion allegedly diverted by current and former employees who gamed an asset-financing scheme.

A boring but time-tested idea is that millions of people give their money to a bank with the promise that they can get it back whenever they want. The bank then lends a chunk of the money for a profit while keeping enough liquidity to meet withdrawals. It works thanks to a mix of regulation, maths, and expensive historical lessons.

For that idea to work at scale, banks must be excellent at three things: figuring out customers’ ability to pay (income, cash flow, shocks) and willingness to pay (incentives, consequences, norms). A bank must also be able to collect repayments at scale: calls, collateral, courts, and time. This third part determines whether your “proprietary model” will survive contact with reality.

When Nigerian banks consider these three factors, they decide that individuals, a.k.a retail loans and small businesses, are not a promising segment.

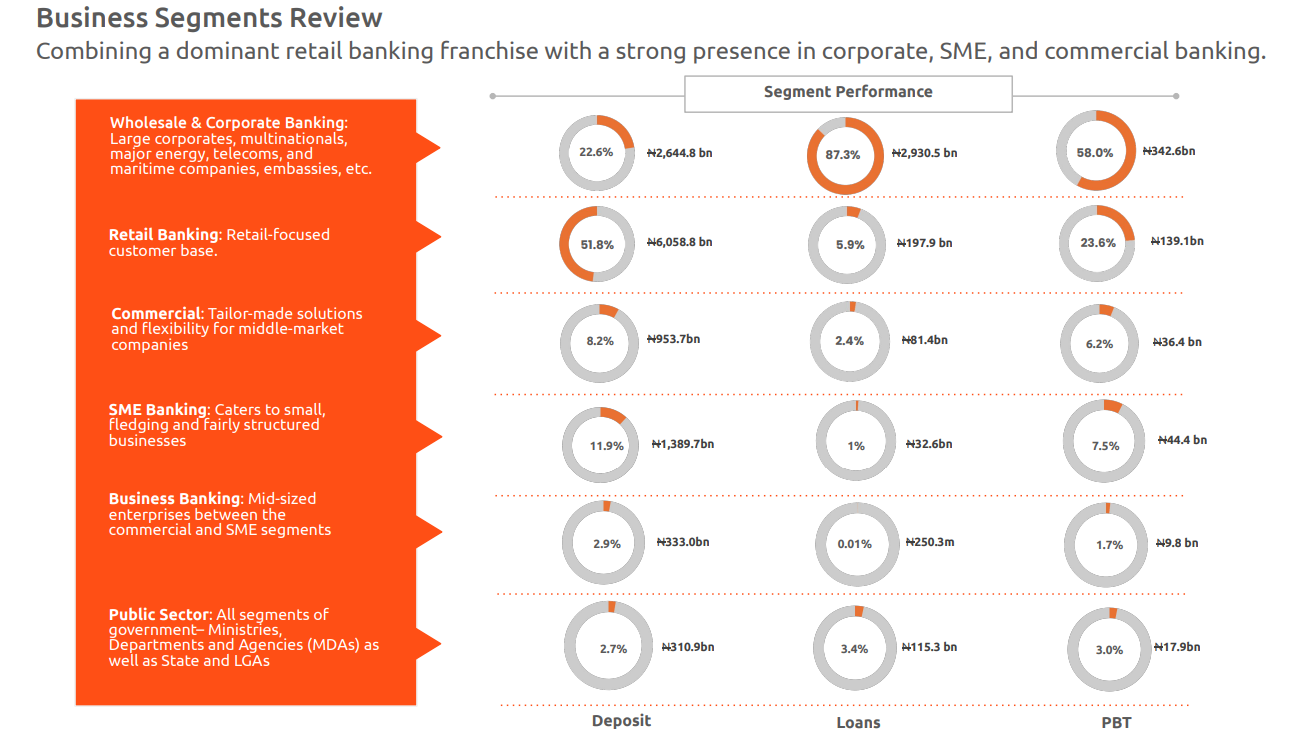

GTCO’s half-year 2025 segment performance shows retail loans make up 5.9% of its total loan segment. SME banking is even smaller at just 1%.

Some of the reluctance to lend to both segments are structural (weak, slow, or inconsistent penalties for default) and some of it is cultural.

I’ve heard about Telegram groups for swapping tips on how to blitz a dozen digital lenders and ghost them. So the banks mostly stay cautious.

Startups looked at the situation and said, “Banks don’t get it. We have the technology.” Banks responded, “We have the scars (and the data).”

In came better data analysis, cheaper distribution, promises of bullet proof decision making models and savvy underwriting for the “underserved.” Classic disruption setup.

Yet the real proof of the pudding in lending is getting your money back promptly.

Take BlackCopper. Their pitch was a superior credit underwriting model for SMEs. Initially, everything looked fine because borrowers treated the first loan like a down payment on a bigger second one. When the “bigger second” didn’t show up, repayments fell off a cliff.

If your collections strategy depends on people getting the next loan, you don’t have a lending model; you have a referral program for defaults.

When the startup was done counting the cost, it owed investors ₦1.2 billion.

Lidya was another well-funded attempt to solve SME lending with better data and product. After ten years and about $16.5 million raised, it shut down this week due to “severe financial distress.”

Yet it’s not all doom and gloom.

In 2023, FairMoney became profitable (₦780 million profit at roughly 1% margin.) In 2024, profit after tax jumped to ₦7.9bn, even after it set aside about ₦59.4bn for bad loans. If you’re not sure what you’re looking at, Fairmoney hacked retail lending by burning cash to learn who pays, then lowering cost of funds so that the math finally worked.

CreditDirect reported ₦4 billion in profits in 2023. It’s difficult but doable.

Yet, every now and then, we’re reminded of the million and one things that can go wrong in retail and SME lending. This week, Access Bank (₦1.21 Trn market cap) approached a Federal High Court to recover a ton of money it lost to current and former staff who gamed its asset financing scheme in 2023.

Here are excerpts from the filing:

“The Applicant is a financial institution and operates an asset loan scheme for its customers wherein it avails its customers facilities for the procurement of assets such as solar and vehicles to ease the smooth operations of its business…some of its staff specifically some of whom were ex-staff, relationship officer, regional manager and branch manager with some customers of the applicant fraudulently applied for asset loans from the bank.”

You already know where this is going.

“Most of the funds fraudulently procured in the guise of asset loans have been dissipated leaving the bank with a total exposure of N4.6 billion.”

Here’s an excerpt from a separate petition to the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC):

“Our review reveals that funds disbursed by the bank meant for the purchase and installation of these facilities were diverted by the vendors to other customers who subsequently transferred funds to accounts linked to staff of the Bank.”

A media relations manager for the bank did not respond to calls and messages seeking comments for this story.

If a tier-1 bank can lose ₦4.6bn to a staff-assisted asset-finance scam, it’s a reminder that people risk doesn’t always fit neatly in a model. Even with controls, insiders can beat the system. And that’s just one more layer on top of everything else you have to solve for in lending: capacity to repay, willingness to repay, and the gamers who repay once to farm a bigger limit and then default. You also need buffers for loan-loss provisioning and the inevitable fraud, plus funding cheap enough that write-offs and collections costs don’t drown you.

So, just how hard is lending?

Postscript: What the numbers teach

Carbon’s old habit of publishing its financial results is useful because it tells a simple story: even in good years, loan impairments ate a big slice of revenue.

In 2018, revenue was about ₦3.73bn and Carbon swung to a profit (~₦147m)—but it still booked ₦2.2bn in net impairment losses. In 2019, revenue rose to $17.5m, yet impairments also climbed to ₦3.14bn.

That’s how consumer credit really works. You make money on interest; you keep it only after you feed the loss monster. Carbon didn’t escape that rule; it learned to live with it.

Kuda’s overdraft is the same lesson. The neobank posted a ₦6.09bn loss in 2021; analysis at the time noted that impairment charges wiped out ~96% of the interest income from its loan/overdraft product. Not long after, Kuda paused overdrafts and its support handle told customers it was “not granting…overdrafts” while it worked to “improve the service.” Today the product is back with tighter terms. Overdrafts looked easy, then the bill arrived; they stepped back, rewired the rules, and tried again.

Consider the Tony Elumelu Foundation. The most prominent banker on the continent funds early founders with grants, not loans. That choice is telling. At the very beginning, the right product may not always be debt; it’s risk-absorbing capital. If even a bank chairman won’t put a loan at the starting line, maybe the banks aren’t “cowards” for avoiding mass retail and SME credit without collateral and teeth. Maybe they’re rational.

And borrowers are not a rounding error; they’re the plot. Studies in Nigeria show the obvious, which people still forget: getting approved helps people; raising the limit doesn’t magically improve their lives. Meanwhile, the street has its own playbook—loan stacking, signal-farming for a bigger second loan, ghosting when the second loan doesn’t arrive. It’s not evil; it’s incentives. Lenders that ignore this write long threads about “unexpected losses.” Lenders that accept it design for deterrence.

Also These:

In a moment that will follow him around forever, Snowflake’s Chief Revenue Officer disclosed material non-public information on one of those “what do you do for a living” TikTok videos.

Flutterwave is making Polygon its default chain for a stablecoin cross-border rail, piloting with enterprise clients this year and expanding to consumers in 2026 across 30+ African countries.

Nigeria’s love of bad ideas continues following the introduction of a new tax on imported petroleum products

See you on Sunday!