Basket Case

From amala to aisle five: the quick-commerce collision course

TOGETHER WITH CREDIT DIRECT

Turn “Come back later” into “Let’s seal it today.”

With flexible Buy Now Pay Later options, you don’t have to lose a ready buyer or delay a purchase that matters.

Credit Direct Checkout makes it easy to buy and sell with confidence, no matter the budget moment.

A few weeks ago, we surprised some lucky Notadeepdive readers with limited-edition t-shirts and journals. (The thank-you emails were the best part.)

Now you don’t have to rely on luck to get yours.

All you need to do is generate your unique link, share Notadeepdive with friends (Whatsapp, Slack, LinkedIn!) and unlock rewards as your referrals stack up.

If you missed last week’s newsletters, catch up here and here.

Exit Stage Left

When Jumia exited food delivery in December 2023, it confirmed a growing belief that food delivery was a fool’s game. At the time, global food delivery companies were bleeding on every drop-off (Uber Eats, Getir, Zomato all found the economics to be brutal), so it wasn’t shocking that Jumia couldn’t create magic with those thin margins.

Yet, Jumia’s departure from the sector wasn’t for a lack of effort. In its heyday, Jumia Food was relentless. Abandon your cart, and a customer care agent would call, probe for the source of friction, and talk you through checkout.

Nnanna sums it up neatly: “Jumia did market education but ran out of energy to serve the market it educated.” For Jumia, food delivery was a vertical, not what it bet the house on; as it came under more pressure to be profitable, it focused on its core constituency: delivering physical goods.

Enter Chowdeck, the sector’s new poster child. It has rewritten the narrative enough to make some people wonder if Jumia’s problem was its operational nous rather than the model.

The storytelling has been immaculate: videos of the popular Amala joint Amoke Oge crossing ₦1 billion in sales; articles about riders earning six figures in a country where the minimum wage is ₦70,000; claims of a customer base north of 1.5 million. The message: This can work if you run it differently. Investors agree.

On Monday, Chowdeck announced a $9 million Series A and claimed it’s profitable (private companies often define that term creatively). The bigger reveal was the ambition to become “Africa’s number one super app” for food, groceries, and essentials.

From lunch to the “nearby basket”

“When a startup gets to Series A, it starts to tell a different story.” - Ridwan Olalere

The narrative of profitability, efficiency, and three million customers ordering Amala instead of pizza and shawarma is nice. But what’s the next step in becoming the “super app” for food, groceries, and essentials?

Chowdeck’s answer is quick commerce. Ultra-fast delivery powered by dark stores, a.k.a mini warehouses, aimed at moving consumers from ordering breakfast and lunch to buying toothpaste, detergent, and other staples delivered in 20–30 minutes.

That delivery time will create a critical shift and will likely mean it can no longer be asset-light. When you need to keep shelves full, you need to own trucks or work with a wholesaler like Omniretail. You’ll also likely need a more dedicated rider pool as you scale.

Look at Uber’s Lagos pivot for a feel of the gravity: when casual drivers weren’t enough, Uber leaned on Moove’s leased, fuel-efficient Suzukis (and drivers required to drive six days a week).

Beyond the fact that delivering household staples drives stickiness, unbundling logistics into neat verticals like food, groceries, parcels, doesn’t create enough value to stand on its own.

The “Uber for X” model has hit the same wall everywhere: Uber does food and parcels; Zomato keeps reaching beyond restaurants; Getir pivoted into groceries. Customers don’t care if a company focuses on one vertical.

They care about convenience, which roughly translates to “do more things for me, right now, in one place.”

As The Economist once wrote about India, grocery delivery in under 20 minutes began as a “ludicrous marketing gimmick” but quickly became a weekly habit for millions.

There’s a trap in that convenience: once customers taste instant, they expect it everywhere and for cheap (see also: Nigerian banking).

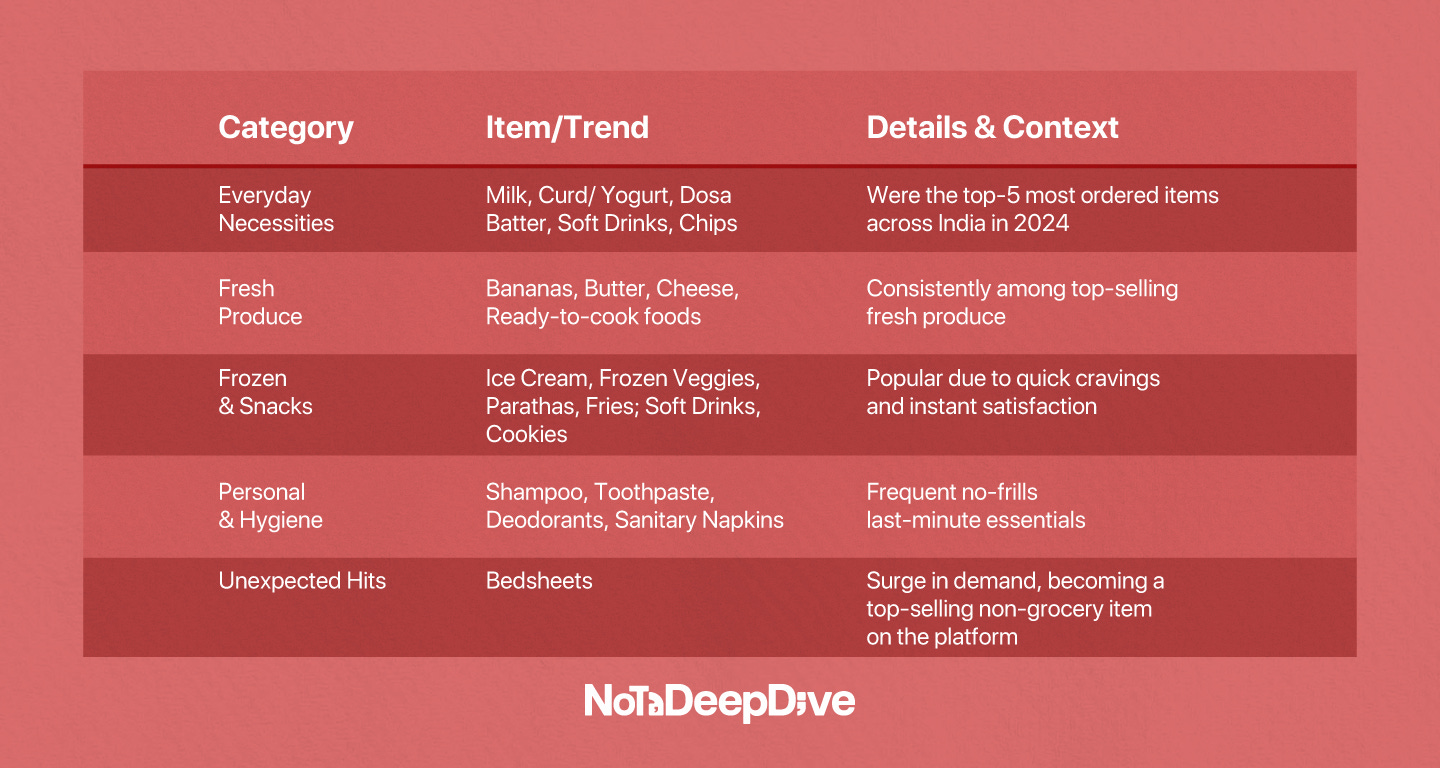

Success in quick commerce comes down to brutal focus: a tightly curated assortment (around 1,000 high-reorder items), placing inventory in dark stores every few kilometres, and routing efficiently enough to make the 20-minute promise stick.

Chowdeck has always offered groceries by listing supermarkets on its app, but from my experience, that’s been hit and miss. Sometimes the listed supermarkets are closed; other times, the items I want are unavailable. That’s why, for me, Chowdeck has mostly meant food delivery, while I turn to other apps or my neighbourhood supermarket for groceries.

Dark stores solve this reliability gap. By holding inventory in small fulfillment hubs, Chowdeck stops depending on third-party supermarket schedules and stock accuracy. If I know an item is available and arriving in 20–30 minutes, I’ll pay the fee nine times out of ten. Marketplace variety is nice, but availability builds habit.

The competition heats up

This shift brings Chowdeck into direct competition with Mano, arguably its most like-for-like rival. Mano already runs quick commerce in Lagos with dark stores that stock physical goods and groceries.

In 2024, it entered food delivery, making its model even closer to Chowdeck’s. But Mano’s geographic focus is narrower, serving highbrow areas in Lagos and Abuja, while Chowdeck’s coverage is broader within the cities it operates in. Mano also charges a flat ₦1,400 delivery fee (2024 figures), giving customers a clear cost upfront.

GoLemon, on the other hand, is in the grocery space. I’ve used it a few times and rate it highly; it now delivers in a day, down from two, and is a reliable choice for staples. Its single-category focus gives it an edge in consistency, but I wonder when it’ll also add on something else to its logistics bundle.

Is the food/grocery delivery sector back in focus? Possibly. And when competition intensifies in a thin-margin industry, consolidation is never far behind.

Bear with me, I had to find a Jumia tie-in

If you stretch the competitive lens, Jumia’s shadow comes into view. If two or three serious players can help millions of young Nigerians form habits around buying physical goods and getting them delivered immediately, Jumia’s moat starts to shrink.

For now, the two companies are running on different tracks. Jumia’s pitch is a broad marketplace with next-day delivery; Chowdeck’s is moving towards ultra-fast and hyper-local.

Jumia’s hubs hold wide catalogues; Chowdeck’s dark stores will run tight, fast-moving items. The overlap stays low until Chowdeck’s baskets shift from ₦3k–₦5k lunches to ₦20k–₦40k pantry items. If dark stores make 20–30 minute delivery a routine expectation, and lunch buyers add pantry items, the notion of a “nearby basket” becomes second nature.

At that point, will the overlap stop at everyday items or will it creep into Jumia’s core assortment, where the average order size is $36.3 (Q2 2025 figures)?

From there, the next logical move is vendor-led expansion into high-velocity non-food: phone accessories, kettles, fans, without heavy inventory risk. Today, the fight is groceries; tomorrow, it could be the categories that power Jumia’s repeat business.

Of course, the counterargument is that once you move from cheap, fast-moving stuff to expensive, slow sellers, you have more cash stuck on shelves, more losses, fewer orders. Ten-minute phone delivery is theatre, not a plan, so maybe Jumia can relax.

And looming above all this is Prosus, the global investor behind Swiggy’s Instamart, now armed with EU approval to acquire Just Eat Takeaway.com, a deal that expands its reach and deepens its grip on food delivery. With Nigeria’s sector beginning to heat up again, it’s hard not to wonder: will Prosus eventually turn its gaze here?

What to watch next

Chowdeck: dark-store rollout pace and on-time rates in rainy season. How will they embed their recent acquisition of Mira into this expansion phase?

Market: Mano, Go-Lemon, Foodcourt, Eden…is the food delivery industry back, or are we going to see consolidation and acquisitions?

Consumer signal: Do lunch buyers add pantry items? does average basket creep from ₦3–5k (food) to ₦8–12k (essentials)?

See you on Sunday! And if you haven’t generated your referral link yet, now’s the time.

This is interesting, but I see a problem when they start to become asset heavy.

When I think marketplace in Nigeria , Jumia, Konga and Jiji comes to my mind. And I’d say Jiji has been the winner, and why; I’d say being asset light certainly helped.