Nigeria’s (Non-AI) Data Centre Wave

Is boring infrastructure a sign of maturity?

If you missed Friday’s newsletter, catch up here. If this email was forwarded to you, subscribe here for free:

TOGETHER WITH CREDIT DIRECT

Life moves fast, but your needs should not stay on hold because access is uncertain.

Credit Direct Checkout lets you make decisions with intention, not pressure. That way, you can stay consistent with the life you are building.

A data centre wave

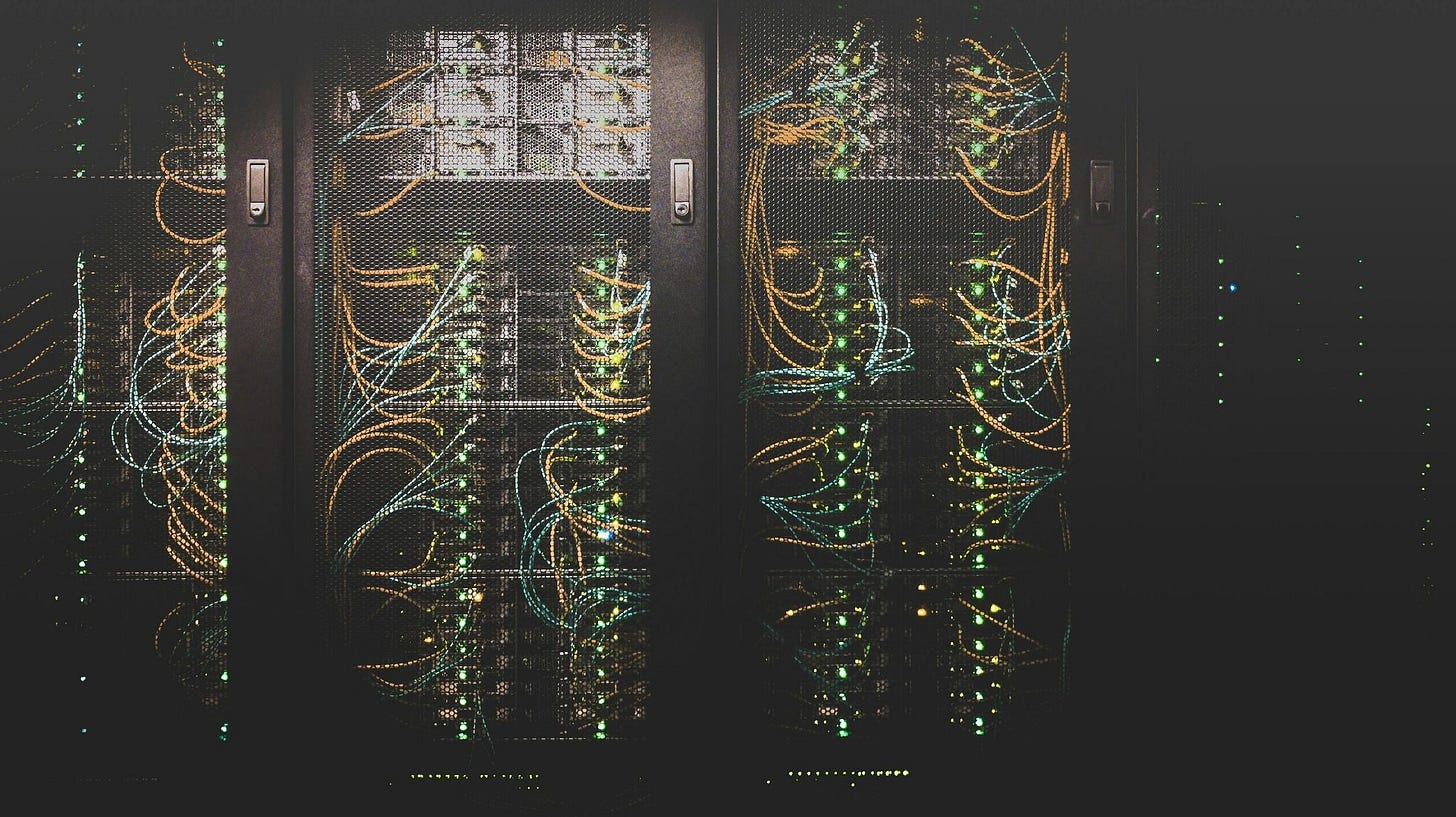

You can’t open a business publication these days without being told that OpenAI, Nvidia, Meta, or Oracle is digging another GPU-powered cave somewhere in the American Midwest. Depending on where you stand, it’s either the Second Industrial Revolution or the most expensive game of musical chairs Silicon Valley has ever played. While that theatre continues, Nigeria is experiencing something quieter but important: a data-centre buildout.

Forget AI for a moment. Nigeria’s digital economy is reaching a point where the foundations finally need to catch up. For years, we stretched the “old model:” on-premise server rooms, telcos doubling as the national compute layer, and a patchwork of engineering tricks to compensate for unreliable power and weak infrastructure.

It worked well enough for payments, banking, and early cloud adoption, but it was always a ceiling. Stephen Deng’s S-curve idea fits here: every digital economy begins by squeezing as much as possible from the legacy setup, but once usage, traffic, and uptime expectations grow, the market has no choice but to shift into the next curve. That’s the context for Nigeria’s data-centre wave.

Over the last few weeks, we’ve seen a sharper uptick in activity: Equinix advancing its LG3 build (a $22m first phase in what is a $100m Africa plan), Airtel’s Nxtra pushing ahead with a 38MW hyperscale footprint in Eko Atlantic, and OADC reaffirming progress on its 24MW Lekki campus, part of a $500m continent-wide strategy. Estate Intel now projects Nigeria’s installed capacity rising from ~56MW today to 200MW+ by 2030, meaning the country is on track to almost quadruple its professional compute footprint within six years.

To understand why all this is happening now, you have to rewind a decade. Companies like MainOne and Rack Centre spent years trying to convince corporate Nigeria that the server room downstairs was not a data centre. The shift was slow but steady: banks pushed disaster-recovery workloads into proper facilities; telcos moved core systems into controlled environments; multinationals made certified capacity mandatory for their Nigerian subsidiaries.

A crucial accelerant was the Central Bank’s requirement that banks use at least a Tier III data centre, nudging even the most conservative institutions toward colocation.

That early demand gave these operators — and MTN, which became one of the largest consumers of third-party capacity — the utilisation and credibility necessary to expand and attract global capital. Rack Centre sold to Actis and then to DigitalBridge. MainOne sold to Equinix.

The second shift came when global cloud and content networks started treating Lagos like a real traffic hub. In practice, that meant deploying more edge nodes in-country, caching content locally instead of backhauling to Europe, increasing peering with Nigerian ISPs and Internet Exchanges, and routing less traffic through Portugal, London, and Amsterdam.

These moves lowered latency, improved reliability, and forced Nigerian operators to upgrade. If Cloudflare, Meta, Microsoft, and Netflix were serving tens of millions of Nigerians daily, they needed Lagos to behave like a proper node, not a distant satellite of the European internet.

The last 24 months, though, represent the true inflection point: the infrastructure investors finally decided that Nigerian data centres could generate stable returns. Their logic is simple:

Long-term contracts with banks, telcos, and cloud providers

High switching costs, because relocating servers is painful

Dollar-linked pricing when possible

Growing digital demand from fintech, e-commerce, SaaS, media and identity systems.

These are predictable, long-horizon cash flows. Exactly what infrastructure capital likes.

So what exactly are Nigeria’s data-centre players building? Colocation facilities; the most basic commercial layer of the data-centre stack. Colocation means keeping your servers in a building designed so they don’t overheat, lose power, get stolen, or go offline. It’s not innovation; it’s the baseline infrastructure every modern economy eventually needs. Think of it as the compute equivalent of industrial parks: boring, expensive, and essential.

Why should you care if you don’t work in telecoms, banking or in the data centre business?

Every banking app, fintech wallet, hospital system, government portal, or Jumia retail site you use sits on servers hosted in a few data centres that only a handful of Nigerians can name. When the physical internet becomes a rental business, those landlords control reliability, pricing (and indirectly) data sovereignty. Also, no one cared about tower economics until it was time to raise data and call prices.

Back to AI. If you’re waiting for Nigerian companies to enter the AI-data-centre conversation, the truth is: the facilities being built today cannot run AI-grade clusters. The power density and cooling requirements are entirely different. But they do lay the groundwork: the land, fibre routes, energy arrangements, and operational maturity that real AI facilities will eventually require.

So if Nigeria ever becomes part of the AI training map, this decade of colocation investment will be a useful preface.

One final note: a handful of Nigerian companies are already tinkering with small, in-house AI-oriented compute clusters. They’re not hyperscale by any measure, but enough to show that the demand for heavier workloads will emerge from the bottom up.

That’s it for today. See you next week!

If this was worth your time, a quick like or comment goes a long way.

Excellent analysis! So easy to get caught up in the AI hype but this foundational data centre work is where the true digital magic starts. A real critical read.

Are there any economic implications (job creation, reduction on enterprise expenses, etc) to having data centres on ground? If any? To what degree. Thanks.